Chapter 2: Half Moon Pose

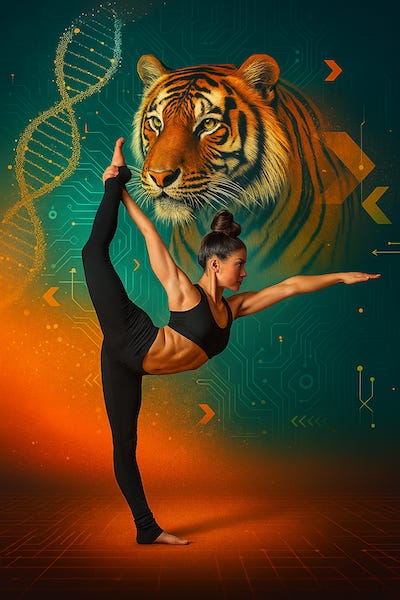

The Broken Moon vs. The Bengal Tiger’s Arc

The Flower That Knew Better Than the Dialogue

“Right shoulder forward, opening your chest like a flower petal blooming.”

The dialogue got one thing right. Sort of.

A flower stem doesn’t hinge when it grows toward light. It creates an arc through phototropism—one side growing faster than the other. The cells on the shaded side elongate more rapidly while the sunny side grows slower. No breaking. No folding. No segments left behind.

The entire stem curves. Globally. Uniformly.

Yet here we are in 105-degree rooms, being told to “push beyond flexibility” and create the exact opposite of what nature perfected over millions of years of evolution. The flower knows what most yoga teachers don’t: sustainable curves come from differential lengthening, not segmental collapse.

Both sides of your spine should lengthen in Half Moon. One side just lengthens more. But common Bikram knowledge says to hinge so you compress and “massage the organs” on one side.

That’s not massage. That’s mechanical ignorance.

When One Student Gets It Right

Picture this: 105 degrees. My class. Twenty-three bodies moving through Half Moon, and finally—FINALLY—one of them gets it.

She’s been listening. Actually listening to what I’ve been teaching about spiral tension, global curves, organizing before moving. Not the dialogue’s “push your hips to the left beyond your flexibility.”

She’s dialing her legs. Creating torque from the ground up. Her spine moves as one global curve—a steel cable under tension, not a stack of poker chips waiting to topple.

After class, she tells me what I hear every day from students who finally understand:

“First time I’ve ever felt stable in that pose.”

A rock climber once told the studio owner everything I was saying about the feet was correct. People who’d practiced for years suddenly “getting” poses they’d only muscled through before. This is what happens when you teach biomechanics instead of poetry.

But first, let’s talk about what “beyond your flexibility” actually means—and why it’s a recipe for disaster.

My Own Broken Moon Phase

Let me confess something.

When I first started Bikram, I was the worst offender. I’d googled pictures of all the postures. I was genuinely impressed by people folding sideways like human origami. Their ears practically touching the floor. Champions, they called them.

I became one of them.

For years, I thought my side bend was impressive. Look how far I could go! Look at that flexibility! What I didn’t realize until I studied fascial science was that I—like those yoga “champions”—wasn’t actually bending. Part of my spine was hypermobile, hinging like a broken door. Other parts? Straight as a board. Stuck. Frozen.

It wasn’t a bend. It was a sideways fold.

A compensation pattern masquerading as achievement. My L3-L4 was taking all the load while T6-T12 did absolutely nothing. I was creating the exact dysfunction I now spend my time fixing in others.

Beyond Your Flexibility: A Dangerous Misunderstanding

Let’s define terms, because the dialogue doesn’t.

Flexibility: Passive range of motion. What you can achieve when gravity or external force moves you.

Mobility: Active range of motion. What you can control with your own muscular effort.

Active End Range: Where you can get yourself and control it.

Passive End Range: Where someone (or something) else can push you.

“Beyond your flexibility” means past your passive end range. Past where your tissues want to go. Past where you have any control. Into the land of plastic deformation where tissues don’t bounce back—they break.

And here’s what nobody talks about: hypermobile people don’t have a real end range. They just keep going until something fails. That’s why rotation is crucial—it creates an artificial end range through muscular tension. When you externally rotate your shoulders (even when “not bearing weight”), you’re creating boundaries. You’re building a container for movement.

Most teachers and studio owners can’t grasp this and don’t want to.

“But they’re not bearing weight with their arms, why do they need to stabilize the shoulders?”

Your body IS the weight. Your spine doesn’t care if it’s a barbell or your own mass. Load is load. Gravity is load. And in 105 degrees, with tissues more compliant than wet noodles, you need MORE control, not less.